By Danny Lim

dannylim@malaysiavotes.com

KOTA BHARU: Where Kelantanese Malays can’t stop offering their opinions on politics, regardless of whether they’re asked, the Chinese community here is rather reticent, even when pushed.

In a vastly Malay state, Chinese voters make up no more than 5% of the electorate in all but three parliamentary constituencies: Kota Bharu, Gua Musang and Kuala Krai. The largest bloc predictably lies in urban Kota Bharu with 17.9%, wherein lies the state seat of Kota Lama which is the only one in Kelantan with Chinese candidates contesting.

Two years ago, I conducted an interview with a Chinese medicine shop owner in Kota Bharu. He couldn’t speak English, and I was useless in any Chinese dialect, so I had the pleasure of conducting an interview where a 70-plus-year-old Chinese man was impressing upon me how “oghe chinoh kelate cukup luar beseh (Kelantan Chinese people are unusual)”.

Indeed, the Chinese assimilation of Kelantanese Malay and Muslim culture, at least superficially, is of a magnitude that is yet unseen elsewhere. My friend Asri tells me of kampung Chinese who wear sarong kain pelikat and pepper their speech with exclamations like “astaghfirullah” (Arabic expression asking for Allah’s forgiveness) and “masha allah” (as Allah has willed).

Even so, political debate in this state remains a largely Malay past time. Amongst the handful of Chinese shopkeepers and hawkers I talk to in Kota Bharu, the common thread is that they’re not too bothered about which party wins (which is not a terribly unusual refrain amongst the Chinese elsewhere either). The ones that are willing to provide a richer, more critical perspective are reluctant to go on record with their names, for reasons of self-preservation.

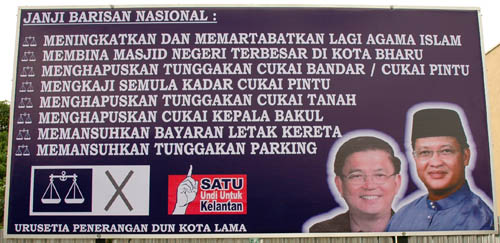

Like one Mr Chan (not his real name), a businessman who says he is helping out in the campaign of the MCA candidate for the Kota Lama state seat, Tan Ken Ten. He speaks like a full-fledged campaign worker, outlining Tan’s credentials: a straight A-student, first class honours Bachelor of Engineering degree, a real “do-er, not a talker unlike (Datuk Haji) Anuar Tan (Abdullah).”

Here Chan moves into discrediting the Chinese Muslim PAS candidate and PAS . “Annuar was a Gerakan member, until PAS came to power, then he joined PAS,” he says. “He is all sweet talk. [PAS] has no solid plan… In politics, rhetoric seems to be more important than actual work. [MCA’s Tan] is not a very good talker. But I know he can do good work and achieve targets.”

One of PAS’s most popular overtures to the Chinese community since the party controlled Kelantan in 1990 was to allow non-Malays access to purchase 30% of Malay reserve land in Kelantan. Chan claims that this move had already been implemented in 1988 in Kubang Kerian when the BN controlled the state and suggests that PAS merely followed the BN’s lead.

He notes the well-publicised annoyances about PAS’s regulations on the limited availability of liquor and pork, as well as the cinema with lights on during screening, but he admits those are “small things”.

“We have been deprived for 18 years,” says Chan, raising his targets. “Our per capita income is one-third of the national average. Infant mortality is high, unemployment is high, we have a drug addiction problem, availability of piped water and proper sewerage systems are limited. Our children don’t come back here to work.”

Chan reads Malaysia Today, as well as many other websites, which he knows are hammering the BN government. “I understand, and agree on certain issues with [these websites],” he says. “But we’re fighting at a different level here. We’re not like in Kuala Lumpur, the west coast, where you’re fighting for ideology. In Kelantan, we’re fighting for basic amenities. Before you talk about freedom of speech, let’s talk about infant mortality.”

A different story

Later on, I meet up for drinks with another Kelantan-born and based Chinese businessman with less partisan inclinations. He too, does not want to divulge his real name, “because I’m doing business with members of both [the BN and PAS]”, so let’s call him Yong.

“[The Chinese community] does not see any problem with the PAS administration,” says Yong. “Although there are lots of comments in the papers that we are discriminated by PAS, but it’s not really true. Eighteen years ago, when PAS took over Kelantan, a lot of Chinese people [from outside the state] didn’t want to come here because they said you cannot eat pork, cannot drink beer. Which is not true. There, what do you call that?” Yong points to the mug of beer in front of me.

“There are lots of things that people assume. At that time (early ’90s) the Internet wasn’t popular yet, so there was a lot of information that outsiders didn’t get,” he says.

“If they don’t agree with PAS, most probably they’re active in the MCA. Those not [politically] active, from what I hear, they’re more for PAS.” He adds that some of the Chinese kampung folks are willing to vote based on how much they can get from the candidates. For example, if one side were to give RM50, and the other side RM100, they would vote accordingly.

The Malay reserve land-buying issue is a double-edged one. As much as it has helped PAS curry favour with the Chinese community, “the BN has used that against PAS, saying that a lot of Malays have lost their land to the Chinese,” he says.

Yong echoes Chan regarding issues like certain amenities, the lack of job opportunities compared to the other states, and the concern of the older generation who see their kids studying out of state and never returning home. “But it doesn’t lead to real dissatisfaction,” Yong insists. “Although there’s not much development, Annuar Tan is popular because he’s friendly and approachable.”

Yong says the implementation of Islamic law is not an issue at all for the Chinese. “That’s only for the Muslims, not for us Chinese,” he says, making an interesting and all-too-common fallacy that the Chinese are exclusively non-Muslims.

“Kampung folks, they’re so used to their own way of life, they don’t care much about other things, and they still don’t believe that with one vote they’ll change the situation.” Yong himself admits that he is usually apathetic about politics. “I just wait and see who will win… what else can we do, get involved in politics?… The Chinese will accept everything that comes, they won’t try to change everything.”

The sense one gets from people like Yong is that those in the Chinese community mostly see themselves as, and allow themselves to be, spectators to the robust political consciousness amongst the Kelantanese Malays. Where the state government has been found lacking, the community has traditionally been self-sufficient and the people ask no more than to be left unimpeded to continue their way of life. Yong says the Chinese ethos is this: “It’s better to deal with the devil that you’re familiar with than to deal with an angel that you’re not familiar with.”

[Note: Kota Lama state seat (N9) is contested by incumbent Anuar Tan Abdullah (PAS) and Tan Ken Ten (BN). There are 27,038 voters; Malay (62.8%), Chinese (34.9%), Indian (1.7%) and Others (0.6).]